Having birds as a pet has become increasingly popular in recent years. According to a survey by the American Pet Products Association, there are around 5.7 million pet bird owners in America based on the 2019-2020 National Pet Owners Survey. If you want to belong to the rising number of pet bird owners, you have to be aware of the avian diseases that could afflict them. These maladies include the polyomavirus in birds.

To know more about common health problems in birds, click this article Bird Health Problems – What You Need to Know About the Types, Treatments, Symptoms, and Prevention.

What is Avian Polyomavirus?

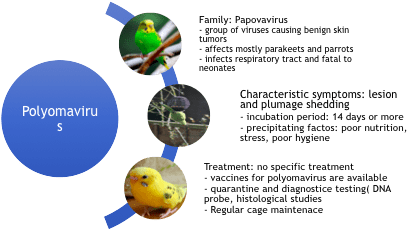

Avian polyomavirus (APV), often referred to as the French molt disease or the Budgerigar Fledgling disease belongs to the Papovavirus family. It causes serious illnesses, and some lead to death in cage birds. This virus is highly contagious and commonly affects many bird species, mainly the psittacines (parrots) and budgerigars (parakeets).

Scientists isolated the first strains of APV during the 1980s from Budgerigars in US and Canada aviaries. They recorded a high incidence of nestling death. Experts note that polyomavirus in birds is notorious among neonates from 14-56 days of age. On the other hand, adults are likely to develop a level of immunity to the virus.

Morphological studies show polyomavirus as a circular, non-enveloped icosahedral (20 faces) virus with a double-stranded DNA genome. Nonenveloped viruses are more resistant to temperature and pH fluctuations, enabling them to survive longer within the host.

What is the mode of transmission for polyomavirus?

It’s difficult to trace the exact path of infection for polyomavirus, but several pieces of evidence show that APV from asymptomatic adults shed the virus via droppings, feather dust, and crop milk (offspring feeding). Healthy birds can contract the disease through direct contact with APV-infected birds. There are also cases of birds acquiring the virus through infected environments, such as in nest boxes or incubators.

Neonates can acquire polyomavirus as soon as they hatch. Nestlings from 10-25 days old up to young adults shed the virus in feces, feather dander, and skin. Studies also show that budgerigar species can directly transmit the virus to the egg.

The incubation period, referring to the time it takes for the infection to develop signs and symptoms, may take two weeks or less in approximation. Death from APV in budgerigars can happen anywhere from 2 to 15 days after birth. Meanwhile, it takes around 140 days for larger parrots.

Young birds can die within 12 to 58 hours after showing clinical signs. However, older nestling surviving the disease can still transmit the virus through fecal matter or feather dander for as long as 16 weeks.

Infection occurs via the respiratory tract, which makes it easy to contract the virus in pet shows or pet shops. Since the virus is environmentally stable, transmission can continue from one year to the next in infected nests.

What are the clinical signs of avian polyomavirus?

Various case studies found four existing strains of polyomaviruses, presenting different clinical signs depending mostly on the age of the infected bird. The most telling sign is feather dystrophy, wherein the chick loses its plumage or fails to develop feathers. In fledglings with growing plumage, a sudden shedding of secondary or tail feathers can occur. There are also some cases wherein the infected bird drops larger feathers but keeps its tail feather intact.

Polyomavirus in birds’ symptoms generally causes a sudden onset of death in young birds aged 10 to 20 days old. Live nestlings can suffer from stunted growth and feather dystrophy, and abdominal distention. Clinical symptoms may involve hepatitis (inflamed liver), hydropericardium (watery fluid in the pericardial cavity of the heart), and ascites (abnormal fluid buildup in the abdomen). Fledglings have a mortality rate as high as 100% when infected with APV.

Some case reports observe bleeding in the bird’s shaft underneath the skin. There are several incidences of associated head tremors from brain lesions, with tremors that can occur 12 to 48 hours before death. Polyomavirus is primarily known as a tumor-inducing agent.

Other signs and symptoms of avian polyomavirus may include weight loss, anorexia, depression, regurgitation, delayed crop emptying, diarrhea, dehydration, wet droppings, and difficulty breathing.

The severity of the APV disease may also vary depending on the species. For instance, a study showed that older parrots could manifest membranous glomerulopathy (inflamed kidneys and decreased function) and sudden mortality. Other species found susceptible to APV include crows, finches, buzzards and falcons.

What causes avian polyomavirus?

Many precipitating factors are what cause polyomavirus in birds. Inadequate nutrition on the breeding stage or overbreeding can strain the bird’s immune system, making them prone to infection. Stress may also play a massive role in the susceptibility of a bird to the disease.

Poor hygiene in the aviary or nest can be another reason for the occurrence of APV. Since bird droppings or feather dust can carry the virus, unclean living space can contribute to infection. Polyomavirus can survive for extended periods in the environment, making it easy for birds to contract the disease when contaminated water and food are lying around.

It is also risky to invite new birds to an aviary or cage. If you are a pet owner or seller, you must be careful about buying, selling and showing pet birds. The APV disease can quickly spread from aviary to aviary just by exposure to carriers and contaminated elements.

How is polyomavirus diagnosed?

The virus may affect all organs, making it possible to perform several diagnostic tests to determine the presence of APV. The veterinarian typically makes an initial diagnosis through a physical exam and DNA probing.

For pet birds, a blood sample may confirm the presence of the polyomavirus via a DNA probe. It can also be done by swabbing affected organs. The DNA probe is a definitive test, which is very reliable in cases where poorly developed characteristic lesions are present.

Histological testing involving inclusions in the skin can help in the diagnosis as well. The bird’s growing feather can feature several lesions, which are then taken samples for testing and confirmation.

Additionally, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests can diagnose the presence of the virus RNA. The samples are taken from oral and cloacal swabs from the infected bird.

In cases of sudden pet bird death, carefully wrap the bird and store in a refrigeration unit until the veterinarian can perform a necropsy on it. The professional can diagnose the APV based on the presence of spores seen in the organs, and the presence of clinical signs and symptoms on the body.

What is the course of treatment for polyomavirus?

There is currently no treatment for polyomavirus in birds. Some veterinarians manage the disease using acyclovir or AZT, which are medications used as polyomavirus treatment in birds. Most infected birds that develop clinical signs will die. The prognosis of the polyomavirus is poor, but some individuals pull through with intensive care.

Surviving birds may shed the virus for as long as six months after infection. It only resolves as the bird reaches its first breeding cycle or sexual maturity.

How to prevent polyomavirus in birds?

If you have an avian breeding facility or aviary, the first thing to do is to quarantine the infected birds and perform diagnostic testing to confirm the presence of APV. Note that older adults can sometimes be asymptomatic, but they are still capable of shedding the virus. Therefore, it is best to isolate them as necessary.

A vaccine for polyomavirus is available for selected psittacines, given yearly during the pet’s annual physical examination. It is typically injected beneath the skin, just over the breast. A booster shot follows the initial vaccine around 2 to 3 weeks after.

Always ensure that the bird’s living area is clean and free of possible contaminants like droppings and feather dust. Disinfect everything that passes from one bird to another, such as feeding instruments, scales, and incubators. You should also wash your hands habitually to avoid transmitting the disease to your pets.

You can use several products to maintain the hygiene of your bird’s cage and other associated living quarters. This Poop-Off Bird Poop Remover easily removes droppings that leave no tiny traces of contamination. It has active enzymes and surfactants that prevent droppings from stubbornly sticking to the surface. You can also try this Bird Cage Cleaner made from plant-based ingredients that are non-toxic and 100% safe for your pet. The bio-enzymatic ingredients break down caked-on particles to give the cage a thorough clean.

Wrap Up

Being a pet parent entails taking on the responsibility of safeguarding the health of your pet. Many avian diseases pose a risk to your pet bird, which is why arming yourself with knowledge and the right supplies are essential. The APV is highly contagious and morbid. But preparation for any scenario can improve the survival of your bird.

When your pet is safe, you can also rest your worries, knowing that illnesses like polyomavirus can’t bring any harm to your pet. Always coordinate with your veterinarian to determine the best course of action when an outbreak occurs. The veterinary professional can guide you through treatment plans and precautionary measures to keep polyomavirus in birds away.

To know more about common health problems in birds, click this article Bird Health Problems – What You Need to Know About the Types, Treatments, Symptoms, and Prevention.